TRACKS, ROADS, FORDS AND BRIDGES IN AND AROUND DORCHESTER (by Ian Gosling)

Roman Durnovaria was serviced by a network of well-maintained long-distance roads built on proper foundations, surfaced with hard wearing materials, such as stones or flints, and drained by side ditches. They were initially constructed for military purposes but proved a boon for commerce and personal travel. The principal roads to and from Dorchester were:

• the Icen Way from East Anglia, through London, Old Sarum, Bradbury Rings, the outskirts of Bere Regis to the East Gate of Dorchester, through the town, out at the West Gate and onwards to Exeter,

• a second road which branched off the road to Exeter close to the town, and ran northwest to Ilchester and Yeovil,

• the road to Weymouth, starting from South Street out through the South Gate, and

• in all probability, a further road linking the town to Wareham and Purbeck.

After the departure of the Romans these roads fell progressively into disrepair since nobody was responsible for their upkeep, although from late medieval times parishes were in principle in charge of their local highways. Consequently, travel became more and more difficult, time consuming and dangerous, particularly in winter because of the ruts, potholes and the regular flooding of river valleys. Travellers on foot, horse or mule, together with herders of animals, continued using the deteriorating remains of the Roman roads, the traditional ridgeways along the chalk escarpments and the countless tracks, principally along the river valleys, many of which predated the Roman occupation.

However, from this period onwards, local landowners started to finance bridge construction to complement and replace fords, and this movement accelerated from the 17th century onwards. Three early bridges still exist today along the pack animal track which runs northwards from the former North Gate and Hangman’s Cottage, two of them next to fords through channels of the Frome. They probably date from the 17th century or earlier (Photos 1 and 2).

There is evidence that the construction of the Great and Little Mohun Bridges which cross the Frome on the road to Charminster, northwards along the old Roman road, were financed by the Moone, or Mohum, family which owned land in Charminster in the 18th century and had previously held the Manor of Wolfeton in the 15th century.

The Great Bridge (Photo 3) probably predates the reign of Charles I who ordered its repair in 1632. It has three arches, a segmental arch built of brick with stone facings flanked by two smaller stone arches. It was reconstructed and widened in 1782.

The Great Bridge (Photo 3) probably predates the reign of Charles I who ordered its repair in 1632. It has three arches, a segmental arch built of brick with stone facings flanked by two smaller stone arches. It was reconstructed and widened in 1782.

The Little Bridge, further north along the road, has three small segmental arches (Photo 4) and was reconstructed in 1775.

Close by, a raised causeway on the side of the road built in the 18th century enables travellers on foot to continue using the road when it floods (Photo 5).  Then, just before Little Burton Mill and the Sun Inn, is a last bridge built of brick with three elliptical arches. It dates from the late 18th century (Photo 6).

Then, just before Little Burton Mill and the Sun Inn, is a last bridge built of brick with three elliptical arches. It dates from the late 18th century (Photo 6).

Then, just before Little Burton Mill and the Sun Inn, is a last bridge built of brick with three elliptical arches. It dates from the late 18th century (Photo 6).

Then, just before Little Burton Mill and the Sun Inn, is a last bridge built of brick with three elliptical arches. It dates from the late 18th century (Photo 6).

Finally, next to the site of West Mills, a two-span bridge of brown brick and Portland Ashlar, built in the early or mid-19th century, carries the road to Maiden Newton (Photo 7).

On the east side of the town the original Roman bridge at East Gate, over the main branch of the Frome on the road to London, had been replaced at an unknown date by a small bridge in Fordington called Stockham or Stocking Bridge, some hundred yards to the east of the Roman bridge.

This in turn was superseded by Grey’s Bridge (Photo 8) built in stone in 1747 and financed by Mrs Lora Pitt of Kingston Maurward House, which reinstated the direct link to the London Road.

Princes’ Bridge, next to the old Fordington Mill and the former Swan Inn, over another branch of the Frome, was built of brick and stone, with two segmental arches, probably in the latter part of the 18th century (Photo 9).

Many of these bridges were built or widened as part of the works which accompanied the building of the Turnpike Roads in the 18th and 19th century. These roads exploited the revolution in road surfacing developed by Pierre-Marie-Jerome Trésaguet, Thomas Telford and John Loudon McAdam from the last half of the 18th Century onwards, and were one of the contributory factors which facilitated England’s industrial revolution.

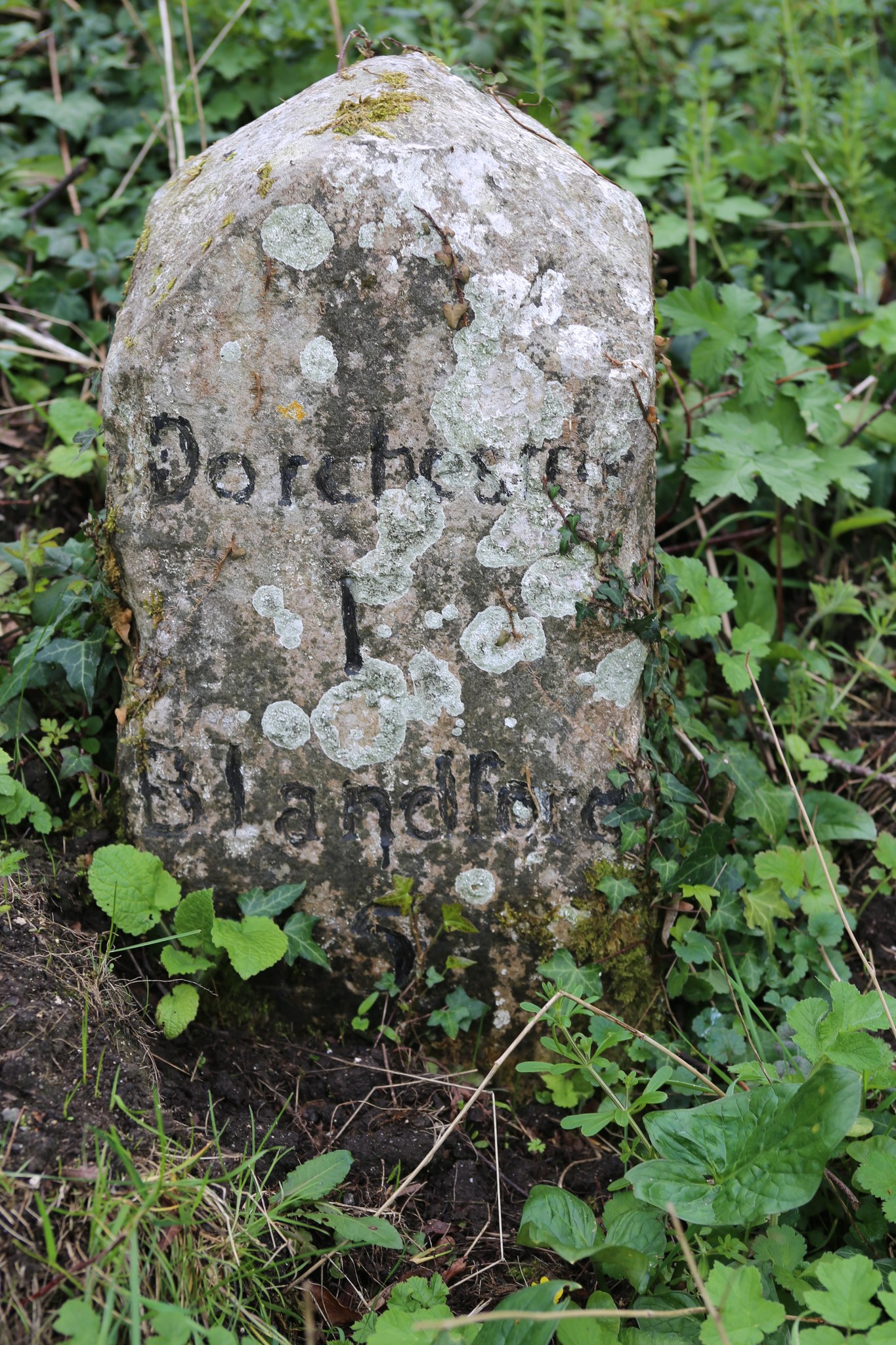

These new roads were often constructed along the routes of the old Roman roads radiating from Dorchester. They were financed by groupings of investors who set up private companies or trusts for each project, often authorised by a private Act of Parliament. The first turnpike, commenced in 1756, was constructed by the Harnham, Blandford and Dorchester Trust and linked Dorchester to Blandford in the east and to Bridport in the west. This was followed in 1761 by a turnpike road from Dorchester to Sherborne in the north, and to Weymouth in the south, constructed by the Weymouth, Melcombe Regis and Dorchester Trust which was established by Act of Parliament. The works involved the upgrading of two of the existing bridges and adding a third new bridge on the road to Charminster. When the road was finished a traveller from the north of the county could enter the town through the West Gate, continue down High West Street and South Street and then exit through South Gate and on to Weymouth.

In 1765 a further Turnpike was planned by the Wareham Trust to link Wareham through Wool, Winfrith, Stafford to Fordington. However, it got no further than Wool and the road was completed by another promoter, the Dorchester and Wool Trust, in 1768 by going through Broadmayne instead. The completed road then linked into the Wareham Trust’s toll road to Spetisbury, which skirted round Charborough Park (now the B3075). In 1778 a turnpike road was opened to Maiden Newton, Crewkerne and Yeovil, built by the Maiden Newton Trust. In 1840 its route was modified to run south of Charminster, instead of running through the village as it had originally done. Finally, A further short turnpike road to Cerne Abbas, built by the Cerne Abbas Trust, came into being in 1824 and the local network of turnpikes was completed in 1841 by a further toll road to Bere Regis and Wimborne. All these roads led directly into other toll roads in the county which enabled travellers to continue their journeys to most main destinations in England, Wales and Scotland.

The cost of construction of these new roads were recouped by their promoters from the tolls charged by them to the horse riders and on the carts, waggons, coaches and herds of animals which chose to travel along them instead of taking the more circuitous and badly maintained traditional tracks and roadways.

The speed and comfort of travelling by road from Dorchester to other major towns in the south-west and to London, and to other destinations was revolutionised by the new bridges and turnpike roads. In 1834, during the reign of William IV (1830-7), the last Georgian monarch, Dorchester had become a hub of speedy road transport:

• the travel time to the capital, via Salisbury, by the ‘Mail’, the daily Royal Mail coach from the King’s Arms, had been reduced from two and a half days at the beginning of the 18th century to thirteen and a half hours. Competition on this route was provided by the daily ‘Magnet’ coach from the same inn and from the Antelope and also by the ‘Herald’ coach from both inns.

• the ‘Royal Dorset’ coach departed to Bristol every alternate day during the week, also from the King’s Arms. The ‘Red Rover’ ran to the same destination on alternate days from the Antelope.

• the ‘Duke of Wellington’ coach ran on alternate days to Bath, again from the King’s Arms, and the ‘John Bull’ did the same from the Antelope.

• Southampton could be reached every day, except on Sundays, by the ‘Emerald’ from the King’s Arms and by the ‘Independent’ from the Antelope.

• the Portsmouth coach, departed from the King’s Arms to Exeter and Plymouth on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays and returned to Portsmouth on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays.

• the ‘Royal George’ to Weymouth was scheduled to synchronise with the arrival of both the ‘Mail’ and the ‘Herald’ from London and it departed daily from both the Antelope and the King’s Arms.

The reduced journey times were achieved by eschewing overnight stops in favour of more frequent regular stops during the journey to change horses, drivers and guards. Long distance wagons carried freight to destinations all over the Kingdom, and local wagons owned by ‘Tranters’ transported both goods and passengers to villages and nearby towns. Wealthy landowners, farmers and the aspiring middle classes took to the turnpikes on horses and in coaches and traps. However, these long-distance coach and freight services met with severe competition from the railways which expanded rapidly in the reign of Queen Victoria, which led eventually to their demise.

This new form of transport reached Dorchester in 1847 when the London and South Western Railway Company line from London to Southampton was extended to the town and Dorchester South Station was opened. Ten years later the Wilts, Somerset & Weymouth line to Bath and Bristol was opened with a station at Dorchester West. Its extension to Weymouth also served the LSWR line from London and Southampton.

IAN GOSLING,

CHAIR OF DORCHESTER CIVIC SOCIETY

Recent Comments