In 1588 Phillip II, the King of Spain, arguably the sovereign of the most powerful nation in the world at that time, launched an armada of naval vessels and merchantmen against England, which was then a minor island state.

England had renounced Catholicism and adopted Protestantism as the national religion, following Henry VIII’s announcement in 1533 of the annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, a Spanish princess. The King had subsequently pronounced himself Head of the Church of England. Mary, Henry’s third child with Catherine, had inherited the English throne as Mary I in 1553, after the premature death of her younger brother who had been crowned Edward VI in 1547. Mary had remained Catholic and in 1554 had married Phillip, then the heir to Charles V the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain, in order to forge a dynastic alliance against France, the rival to Spain and hereditary enemy of England. Mary had died childless in 1558 and the throne had passed to her younger sister Elizabeth I.

The objective of the expedition was to overthrow Elizabeth I, reinstate Catholicism to England, end the attacks by English privateers against Spanish vessels trading with the New World and the support given by England to the United Provinces in Holland to secede from Spanish rule. Pope Sixtus V undertook to support the expedition financially and declared it a Crusade.

The Spanish fleet was commanded by Duke Medina Sidonia after the unexpected death of the experienced Admiral Santa Cruz. Duke Medina was a senior aristocrat and experienced soldier but, critically, had no naval experience.

After its banner had been blessed by the Pope the fleet set sail from Lisbon on 21st July 1588 and headed for the English Channel. After a halt at Corunna for repairs it was comprised of a total of 137 vessels of which purpose-built warships accounted for just over half, with 24 heavily armed warships, 38 auxiliary vessels and 34 supply ships. The plan was to secure the channel and the south coast of England to allow an army of 55,000 men to embark in boats from the remaining Spanish part of the Netherlands and to then land on the English coast.

The English fleet, based in Plymouth, comprised 34 ships from the Royal fleet together with 163 other ships, 30 of which carried up to 42 guns each. Amongst the fleet were 12 privateers, including Golden Hind owned by Francis Drake.

Amongst The most significant warships in the Armada was the San Salvador (the vessel in the foreground of the representation of the fleet in a contemporary tapestry – Photo I is of a print reproducing the tapestry before the latter’s destruction).

In Spanish terms she was of 958 tons, armed with 24 guns, manned by 90 mariners with a normal complement of 281 soldiers, increased very considerably by troops who were on board to take part in the invasion. She was the Vice Flagship of the fleet and also carried some 50,000 gold sovereigns from the Spanish Royal Treasury to fund the invasion.

As explained below, this vessel is what potentially links the Armada to Dorchester.

The Armada was spotted off the Lizard on 29th July. A first engagement took place next day off Plymouth near the Eddystone rocks, when neither side lost any vessels.

The following day the two fleets engaged once more, off Portland Bill. At around 3pm a large explosion took place on board the San Salvador and she sustained extensive damage. Contemporary sources report that the aft (rear) castle, and the two decks below, were blown out and 400 of the men on board were killed, severely burnt or drowned as they sought to escape. Most of the fires aboard were extinguished, preventing the explosion of the main powder magazine, and part of the survivors were taken off and transferred to the fleet’s hospital ship. The stricken vessel was then towed to the centre of the Spanish fleet.

It is uncertain what caused the blast. One possibility, which was widely believed at the time, was that a German gunner set light to some barrels of gunpowder and then threw himself overboard as an act of revenge against a Spanish officer who was having an affair with his wife who was also on board! An alternative explanation is that the gunner had been disciplined by the captain for his poor performance, but the most likely reason is that a spark from a burning wick used by the gunner to fire successive rounds was blown onto barrels of powder on deck next to the guns.

The vessel proved impossible to repair and was taking on water, so the next day the decision was taken to scuttle it. A team was sent aboard to recover the treasure of gold coins together with the cannons, and then sink the ship. They were unable to do anything, the coins being “in the ballast with the collapsed decks on top of it”, the guns impossible to shift and the vessel proving impossible to sink. As the English fleet was closing in, the Spaniards were obliged to abandon the San Salvador, in their haste even leaving some fifty of the wounded on board, including the gunner and his wife.

Later that day a prize crew commanded by John Hawkins boarded the vessel but found “the stink in the ship so unsavoury and the sight within board so ugly” they left it to be towed to Weymouth by Drake’s Golden Hind.

There the records show that she was stripped of her cannons, powder and shot. There is however no record of any of the oak timbers of which she was constructed having been removed, despite seasoned oak being highly valued at the time. It is highly likely however that some timbers were removed, if only to make the remaining vessel more ship-shape. The fact that this is not recorded is not altogether surprising since there seems to be no evidence that the hoard of gold coins was found either, which, given their value, is very curious!

A few days later, after some summary repairs, she set sail for Plymouth in the hands of a skeleton crew but foundered off Studland, after the rescue of most of the seamen. The fact that she was wrecked to the east of her port of departure, rather than to the west where she was heading, would indicate that she met with a strong westerly wind and heavy seas and was unable to beat into that wind because of her fragile state, and perhaps because she was undermanned.

In the winter of 2000-2001 a substantial piece of timber was washed up on Studland Beach and recovered by the National Trust. Three further timbers were then washed up in 2002. These may all be from the wreck of the San Salvador which is lying on the seabed offshore.

It is believed that boys from Hardye’s school in Dorchester saw the Armada, perhaps from the Ridgeway, as it sailed past the Dorset coast at the end of that month of July. This is quite possible given that school must have broken up at harvest time to enable the pupils to help bring in the crops.

Hardye’s School is reputed to have been founded in 1569 by Thomas Hardye of Melcombe Regis, although it may well have existed for some time before then. The founder built new premises for the school on the site now occupied by Hardye Arcade in South Street and provided it with an endowment financed from the income from his land to pay a graduate to act as the headmaster.

The school buildings were destroyed by the Great Fire which ravaged the town in 1613. It was then rebuilt under the direction of the then headmaster Robert Cheeke in 1618, financed by public subscription of the inhabitants of the town. An oak screen was installed in the school room and tradition has it that it was constructed from timber taken from the San Salvador, and specifically from its aft castle.

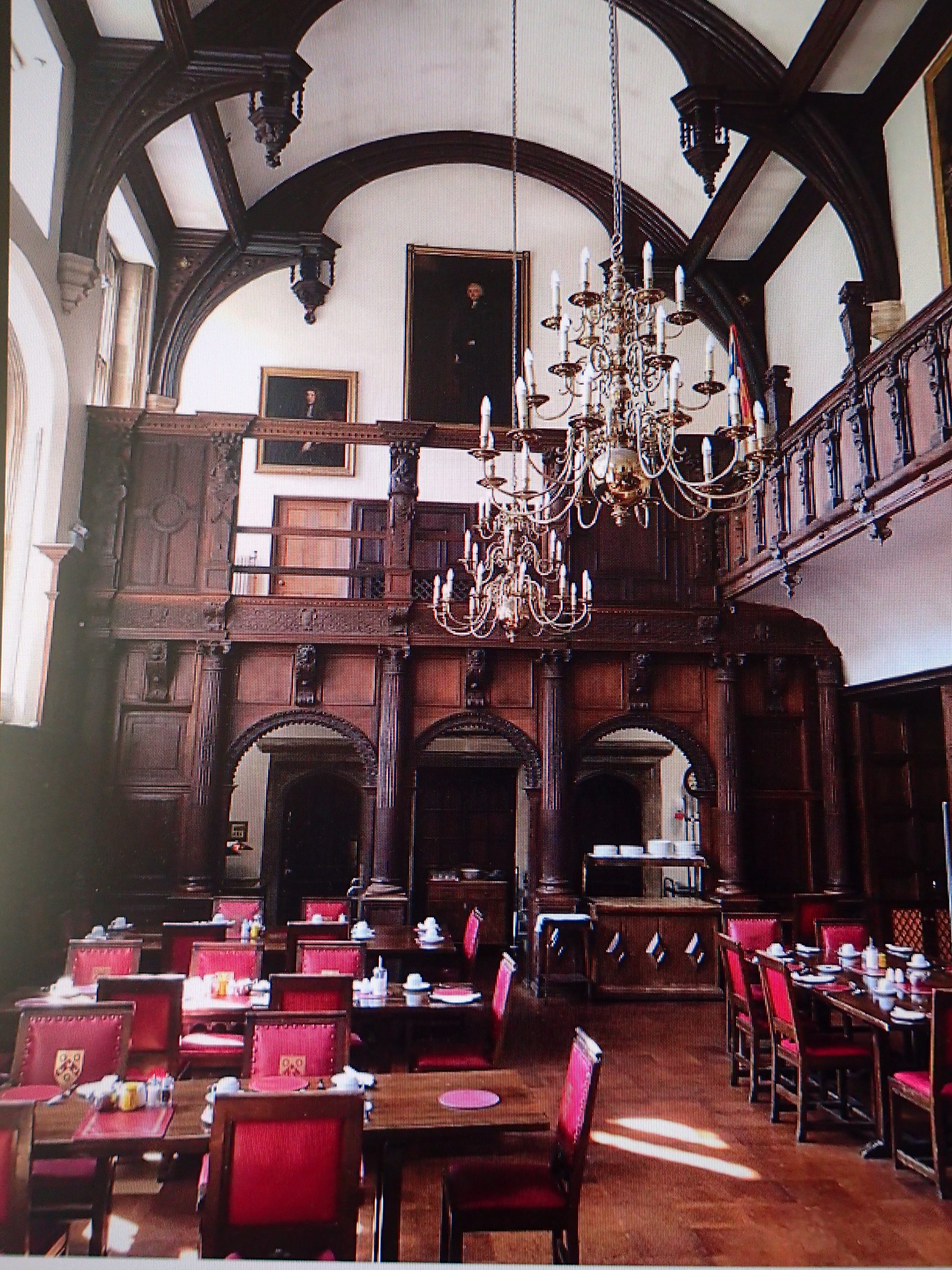

The screen remained in the school, and moved with it to its different sites, until it ended up displayed above the stage in the theatre in the present school premises in Queens Avenue. When work was started on refurbishing the theatre in 2021 the screen was removed and put into store. As result of a misunderstanding, it was disposed of and then spotted by a restoration specialist in June last year whilst it was awaiting sale in a Cambridgeshire sale room. The Hardyeans’ Club raised the funds necessary to buy back the screen and it is now undergoing restoration work in the Jubilee Hall in Poundbury (Photo II).

I had the privilege of examining it a month ago.

Is this screen made up of panels from the aft castle of the San Salvador or is it from another captured vessel from the fleet? Alternatively, was it removed from the walls of a mid-17th century hall in England and reused when the school was rebuilt in 1618?

The task of determining the origins of the panels is made very difficult because the style of carving and decoration figuring on hall screens and on the “castles” of prestigious warships was similar in England and the continent. At the time however the whole of the exterior of the castles and hulls of such naval vessels would have been coated in brightly coloured paints whilst land-based screens would have been discreetly tinted or polished.

The first hypothesis that the screen is made up of elements taken from the aft castle of the San Salvador is the explanation that has been handed down the generations. It is supported by the analysis of the type of wood which showed it to be mediterranean oak rather than English oak. However, if they were taken from panels of the aft castle of that ship, and re-utilised much as they were on board, they could only have been taken from the front facing façade of the aft castle since the screen has two door openings near to one another, similar to the arrangement on some such ships and no window openings or gun ports which would be likely to exist on side panels.

The major obstacle to this theory is that the eyewitness accounts clearly report that the aft castle was blown out by the explosion and therefore its deck frontage would not have survived, or done so only in a very damaged state. Moreover, the screen’s wood is not visibly damaged by the percussive force of an explosion and of the flying debris which it would have created. However, a part of the timber surface on the reverse side of the middle section of the horizontal frieze, halfway up the screen, has scorching marks and craquelures such as might have been caused by the fire which followed the explosion. It is worth noting that the two doors open outwards, which they would have done on a boat in order to prevent waves of water on the deck in heavy weather from penetrating into the castle, although of course the hinging arrangements could have been altered when the screens were installed in its first location or when moved to the school. Finally, I saw no visible traces at all of any residue paint or other possible water proofing treatment in the fibre of the wood.

It is also conceivable that the screen might have been created out of undamaged planks and timbers taken from other parts of the aft castle, some perhaps carved, and further matching carving carried out on the screen when it was constructed from the timber by English craftsmen.

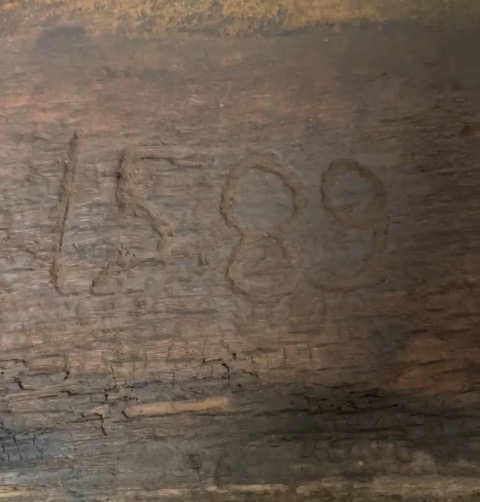

The carved date of 1589 found on the scorched panel on the reverse side of the screen would seem to indicate that it was applied by an English joiner creating the screen in a first location in the hall of an existing building (Photo III). The names of various school pupils added over the centuries to the face of the screen should of course be completely disregarded!

Could the screen have been made up of wood taken from another captured vessel in the Armada. Possibly, although all the stylistic and technical objections listed above would tend to make it unlikely.

In order to advance either of the above theories, it would be necessary to undertake further technical analysis of the screen with all the modern investigatory techniques available to establish the age(s) of the woods used, the exact region in which they grew, whether there is any evidence of damage from seawater or paint or other residues in the fibres, and, in the affirmative, an analysis of any pigments or residues surviving in the wood.

It would also be helpful to carry out a study of all contemporary existing drawings, prints or paintings of the superstructure of Spanish naval vessels. As far as I am aware it was not the practice at that time to make shipyard models of boats before or after they were constructed so none would be available.

Turning to the last option, that the screen was removed from a preexisting building and transferred to the school, the layout of the Hardye Screen and the style of the carved architectural details which decorate it, reminded me immediately of the carved Elizabethan period screen installed in the hall of Grays Inn in London a few decades after it was completed in 1559, and where I read for the Bar (Photo IV).

These screens were installed in the late 15th to early 17th century in Great Halls of grand country and town houses, and also in public buildings, to form an entrance vestibule to separate the outside entrance to the Hall from the main room. They acted as draft excluders and enabled visitors to shed and leave their coats and riding boots. Quite often they were installed in pre-existing halls and were decorated with columns and carved features in the renaissance style in fashion at the time on the continent of Europe and the British Isles. Sometimes, the platform created behind the screen to serve as the ceiling to the entrance vestibule served as a stage for musicians during receptions and ceremonies in the hall below.

There is a similar, but much simpler screen in the Charterhouse Hall in London (Photo V) and, much nearer to hand, there is a much earlier and plainer example (15th century) in the Great Hall in Athelhampton House near to Dorchester (Photo VI).That latter screen originated in Devon and was installed in 1899 when the House was restored following many years’ use as a farmhouse, during which the original screen was removed.

The similarities to the Grays Inn screen are striking and it is interesting to note that it is reputed to have been made from wood taken from a Spanish galleon from the Armada fleet and given by Queen Elizabeth I to the Inn. There is however no supporting source material to confirm this tradition.

The Jury is out! However, but whatever its origins, the Hardye Screen is an important part of Dorchester’s history, and independently from that, an important heritage asset. I believe that its future must be assured, and it should be displayed and conserved within the town in a place where it can be seen by the public.

At present it belongs to the Hardyeans’ Club which is raising the funds necessary to complete its restoration and has launched a crowd funding appeal online on the JustGiving page.

https://www.justgiving.com/crowdfunding/TheGreatOakScreen

Please check it out and make a contribution towards the £15,000 needed to complete this vital conservation project.

Ian Gosling

23.5.2024

Recent Comments