FROM RAILWAYS TO MUSEUMS (By Ian Gosling)

Last month I concluded by showing how the arrival of the steam age and of the railways in Dorset sounded the death knell of long-distance travel by stagecoach from Dorchester.

However, the revolution did not happen overnight since the construction of the railway lines and the building of Dorchester’s two railway stations proved a lengthy and laborious enterprise.

It all started in 1845 when Henry Castleman, a Wimborne solicitor, acting as the leading promoter, petitioned Parliament to pass a private Act to enable the Southampton and Dorchester Railway Company to construct a line between the two towns and to lease or sell the business to the London and Southwestern Railway Company. The construction of the line proceeded rapidly and was opened, together with Dorchester South station, on 1st June 1847. By then the promoting company had been taken over by the L&SWR.

In the same year 1845, the Wilshire, Somerset & Southwestern Company promoted the construction of a line from Chippenham, through Westbury, Frome and Yeovil to Dorchester and Weymouth. This project too was taken over, this time by the Great Western Railway. Work started at the end of the 1840s and was engineered by Isambard Kingdom Brunel. There was vocal and organised opposition from a group of gentlemen to the initial plan to carve a cutting though Poundbury Hill Fort and to raze part of Maumbury Rings to facilitate the construction of this railway line.

This opposition obliged the company to construct a tunnel through the Hill Fort and to deflect the alignment of the route from Dorchester to the south of the Rings. As a result, the junction with the L &SWR line had to take place to the south, rather than in the existing Dorchester South railway station which acted as the terminus of the line to London.

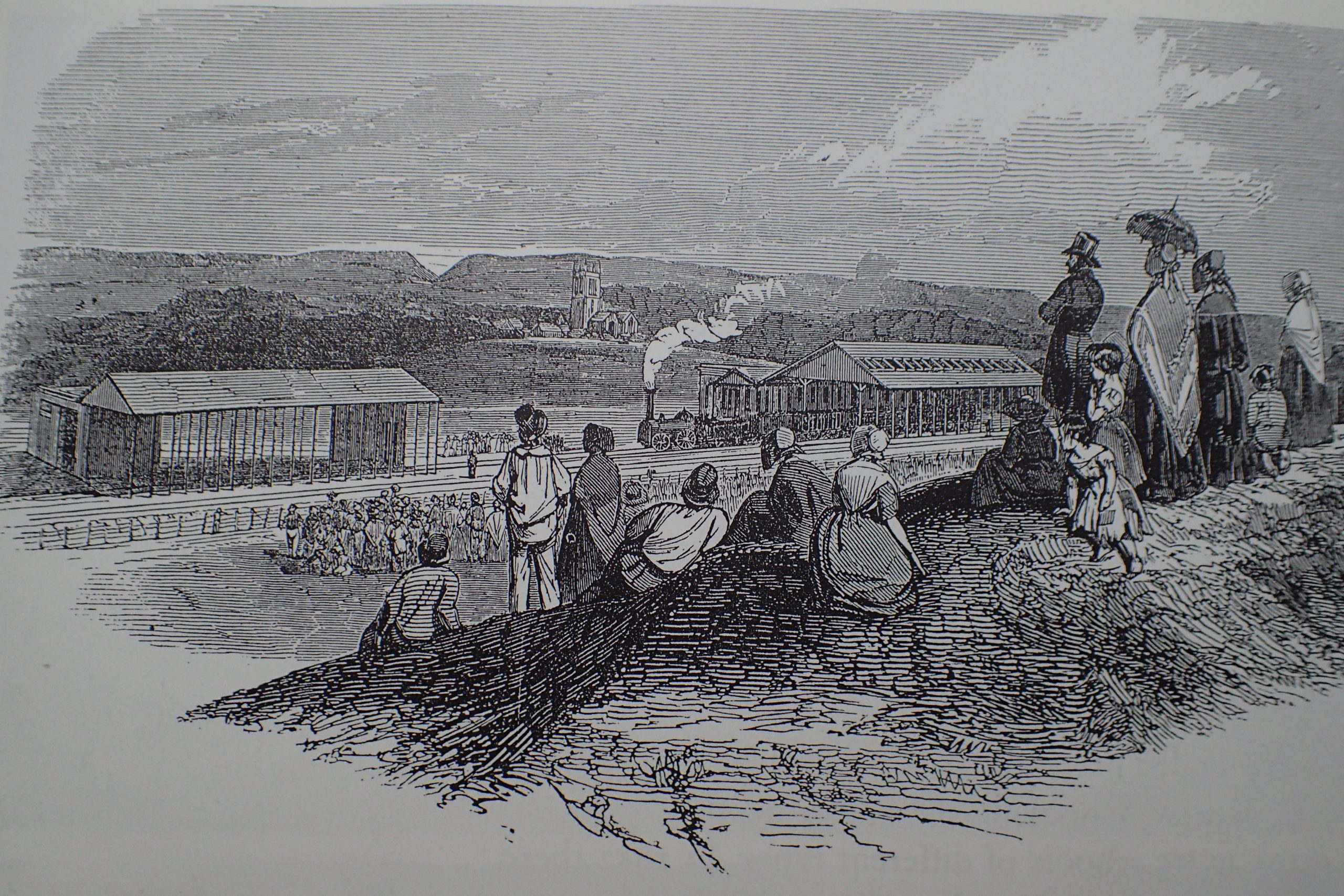

Consequently, for many years trains to and from London had to back in and out of Dorchester South station if they had arrived from or were departing to Weymouth (Photo 1. of a Victorian print of a train leaving the South Station).

A further complication was caused by the fact that the line to Southampton had been built in what was then called “narrow- gauge” track whilst the line built by Brunel to Dorchester West station was in a wider gauge known as “wide- gauge”. Consequently, the line to Weymouth had to be constructed in twin, or double- gauge, to carry trains both from Southampton and from Wilshire. The narrower of the two gauges became the “standard- gauge” when it was adopted by the Gauge Act of 1846. As a result, GWR progressively replaced its early broad-gauge track to standard -gauge and finished the process only at the end of the century.

Because of all these complications Dorchester West station only opened to the public in 1857.

As in heyday of stagecoach travel passengers embarking at Dorchester’s railway stations could access other towns throughout the county and beyond, either directly or by changing stations. For example, by 1875, branch lines ran to Bridport/West Bay and to Abbotsbury and mainline trains ran to Exeter, Bristol and Bath.

The principal part of the booking hall at Dorchester West station (Photo 2.) is the original building erected by Brunel, in red brick with plaster pilasters. Unfortunately, the original wood canopy which spanned over the track to the opposite platform no longer exists, but the booking hall which remains is listed as a Grade II Listed Building. An outstanding example of a Brunel canopy survives at Frome station.

The principal part of the booking hall at Dorchester West station (Photo 2.) is the original building erected by Brunel, in red brick with plaster pilasters. Unfortunately, the original wood canopy which spanned over the track to the opposite platform no longer exists, but the booking hall which remains is listed as a Grade II Listed Building. An outstanding example of a Brunel canopy survives at Frome station.

The group of gentlemen who opposed the initial route of the Great Western railway Line are the link between the construction of the railways and the formation of Dorset County Museum.

On 15th October 1845 this group, spearheaded by the poet, writer and schoolteacher William Barnes, the Vicar of Fordington the Rev Henry Moule, and the Rev C.W. Bingham decided that the ancient artifacts and natural history specimens which would be unearthed by the proposed railway works should be preserved and that it would be “advisable to take immediate steps for the establishment of an institution in this Town, containing a Museum and Library for the County of Dorset”.

In fact, antiquarian interest in the geology, natural history, archaeology and the early history of the County had been steadily increasing from the beginning of the 17th century.

John Aubry (1626-1697) was born in Wiltshire and educated at Malmsbury Grammar School and at Blandford Grammar School in Dorset before studying at Trinity College Oxford. He devoted his life to archaeology and the study of the early history of England and worked on county histories of both Wiltshire and Surrey. In 1649 he discovered the important remains of the Megalithic site at Avebury Rings in Wiltshire. This led him to publish his important antiquarian work “Monumenta Britannica” and he subsequently became a member of the Royal Society and can claim to be the father of British archaeology and the study of antiquity.

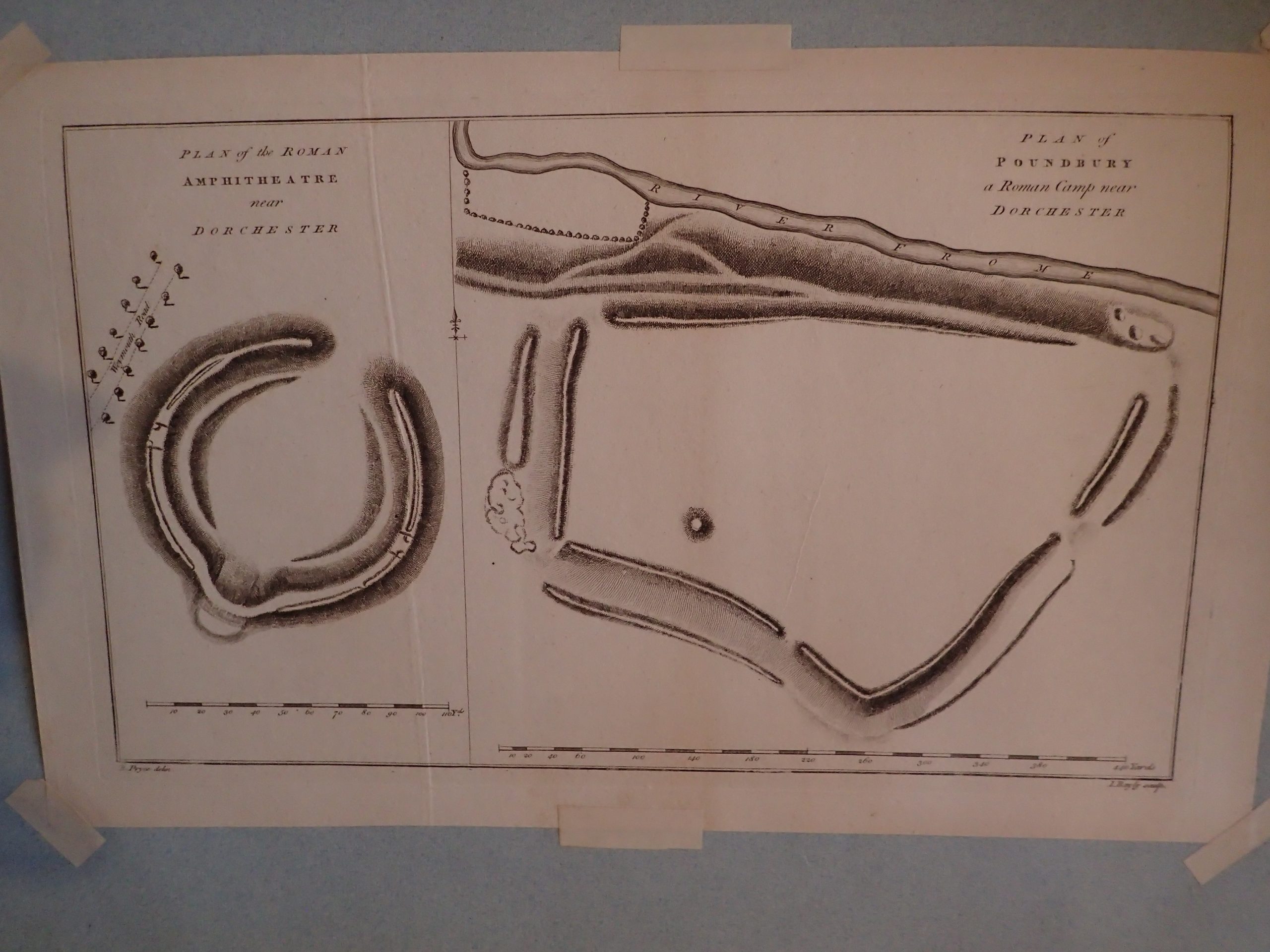

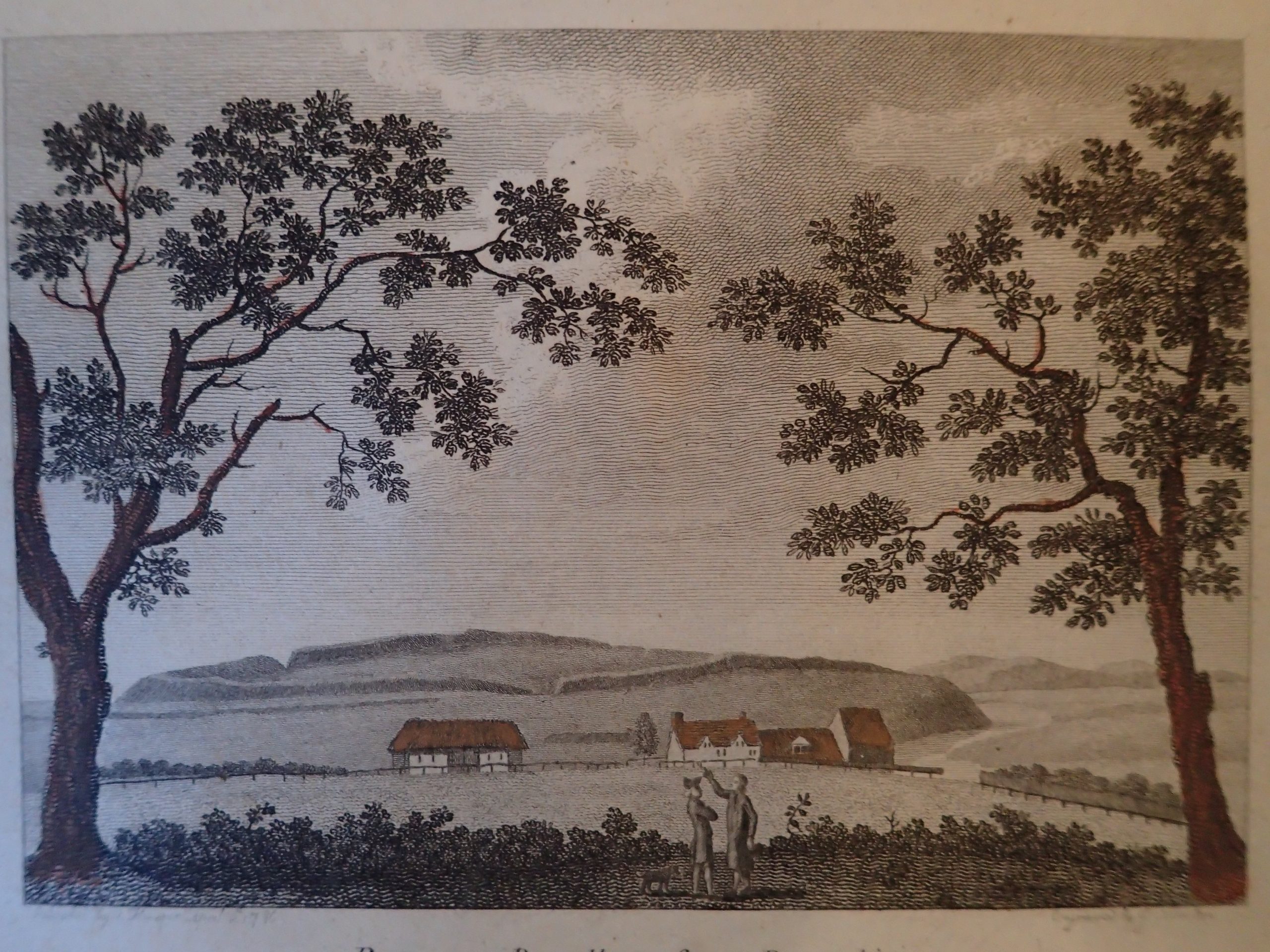

William Stukely (1687-1765) was one of the many who followed in his footsteps. He visited Dorchester in 1723 as part of a tour of the West Country which he wrote up under the title of “Iter Dumnonsiense and Iter septimum Antonini org”. He also wrote a separate study of Maumbury Rings in October of that year under the title “Of the Roman Amphiheater at Dorchester”. These works were accompanied by engravings, including of Maumbury Rings (Photo 3.) and Poundbury Hill Fort (Photo 4.).

John Hutchins (1698-1773) was born in Bradford Peverell just outside Dorchester and studied at Dorchester Grammar School and at both Oxford and Cambridge Universities. He was was ordained and appointed Vicar of Milton Abbas and then Rector of Swyre and of Melcombe Horsey, before becoming Rector of Holy Trinity in Wareham in 1744, whilst retaining his other two benefices.

Encouraged by Jacob Bancks of Milton Abbey he dedicated his life to researching and writing his history of the County of Dorset, the first edition of which was published in two volumes the year after his death.

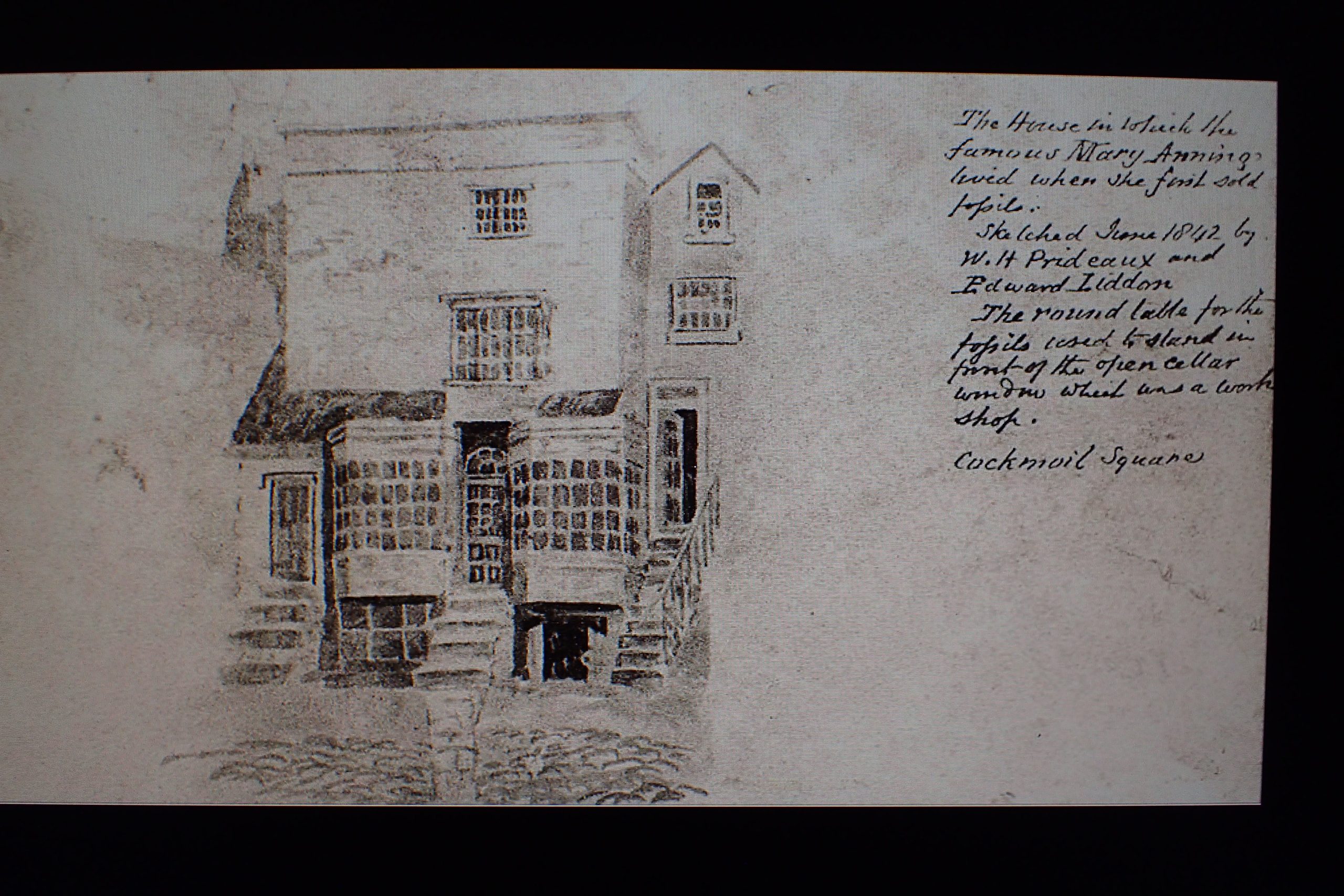

Finally, Mary Anning (1799-1847) the fossil collector who lived in Lyme Regis took over the management of the fossil shop founded by her parents (Photo 5 of a drawing of the shop) and, despite a very rudimentary formal education, became Europe’s most celebrated palaeontologist.

The “Gentlemen Protesters” in the 1840s were following on in the footsteps of these illustrious predecessors who had awakened interest in the County’s past, when they resolved to preserve the evidence of it which was being uncovered by the railway construction works in a permanent museum which would be open to the public.

As a first step in 1846 the fledgling collection of the Dorset Field Club which they had formed for that purpose was housed in two rooms in Judge Jeffreys’ Lodgings in High West Street. Then in 1851, when the collection was outgrowing the space available, the Club resolved to rent a house in South Back Street, now called Trinity Street, adjacent to the Antelope, both of which were owned by Robert Williams. The house had become surplus to the family’s requirements since the improvements to the road from Dorchester to Bridport enabled them to return home on horseback, or by carriage, to their mansion at Bridehead, instead of staying overnight in the County Town. The house was rented for a term of 21 years at an annual rent of £30, reduced from the market value of £40 by reason of the involvement of the Williams family in the development of the museum.

In addition to housing the museum, it contained a reading room and was staffed by an attendant and his family, who was required to act as the “Curator”. The attendant had use of the rooms not required for the museum for his family’s accommodation and was paid £12 per annum to “provide gas and coal of the best quality” to light and heat the house.

This function soon gave rise to difficulties since the first appointee left “suddenly” in 1853 and “absconded” to Australia leaving his wife behind. His successor was no improvement since he had to be dismissed due to his “intemperate habits”!

The census of1861 reveals that the attendant at that date was a Mr James Orchard who described his occupation as being a “clerk”, and the 1871 census shows that he had been replaced by a Mrs Ellen Voss.

That same year Dorchester’s School of Art approached the trustees of the Dorset Field Cub Museum to propose an amalgamation which “might secure a better building for this joint purpose”.

As a consequence, the museum trustees set up a special committee with Arthur Williams as Secretary. Robert Williams, who was the M.P. for Dorchester from 1812 to 1835, offered the site of “The George” inn in High West Street for the construction of a new purpose-built museum which would also house the Working Men’s Institute.

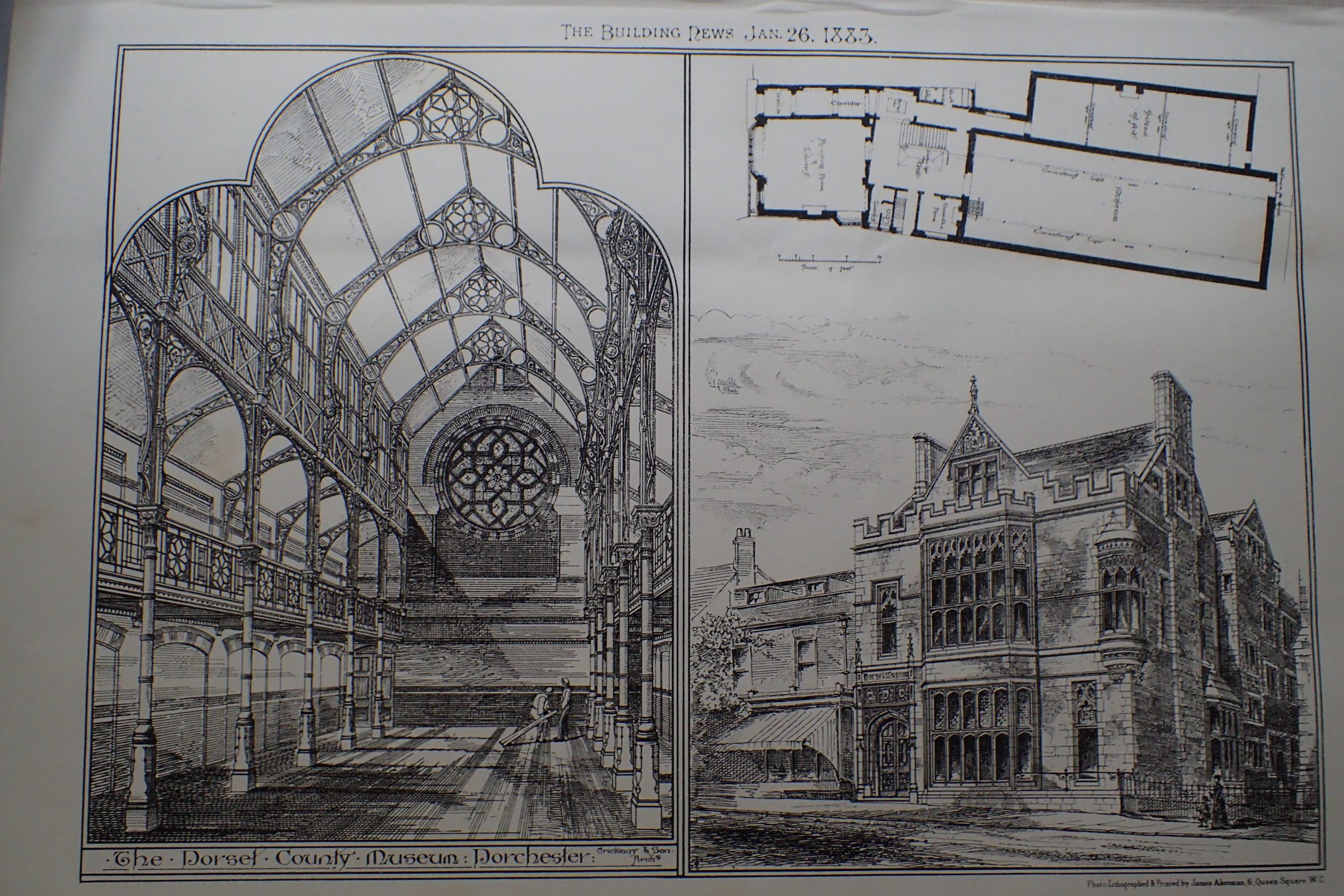

The works were to be funded by public subscription and the architect G.R. Crickmay was instructed to prepare plans and elevations of a new building on the site of “The George”.

The new building was completed and fitted out during the course of 1883 and the museum was open to the public in 1884 (photo 6 – Drawing of the façade and of the main hall together with a site plan, published in the “Building News” of January 26th, 1883).

Meanwhile in 1881 the trustees had appointed Henry Joseph Moule, one of the sons of the Rev. Henry Moule, to catalogue the collection, to prepare its move to the new building and to run the new museum. His initial salary was £50 per annum as from the museum’s inauguration.

H.J. Moule was a self-taught but skilled water colourist, antiquarian and author. He was a close friend of Thomas Hardy and taught him to paint in water colours.

Henry Moule was offered the former museum in Trinity Street as the family home for his wife and children, Henry Reginald, John Fredrick and Madge. In a letter to his solicitor written from his lodgings in High East Street on 13th November 1883 he informed him that “We are in a few weeks to go into a house in Trinity Street”. There he frequently entertained Thomas Hardy. They worked together on a project to produce a book on Dorset for which Hardy was to write the text and he was to create the illustrations. Unfortunately, the proposed collaboration never materialised. Instead, Henry Moule wrote a number of books himself, including “Old Dorset” (1893) and “Dorchester Antiquities” (published in 1901 and then again posthumously in 1906). He died on 13th March 1904.

In Thomas Hardy’s “The Mayor of Casterbridge” published in 1886 Lucetta Templeman, the lover of the main character Michael Henchard, sends his daughter to visit the town’s museum in Trinity Street.

It is described by Lucetta as “an old house in a back street – I forget where – but you’ll find out – and there are crowds of interesting things – skeletons, teeth, old pots and pans, ancient boots and shoes, bird’s eggs – all charmingly instructive. You will be sure to stay till you are quite hungry.”

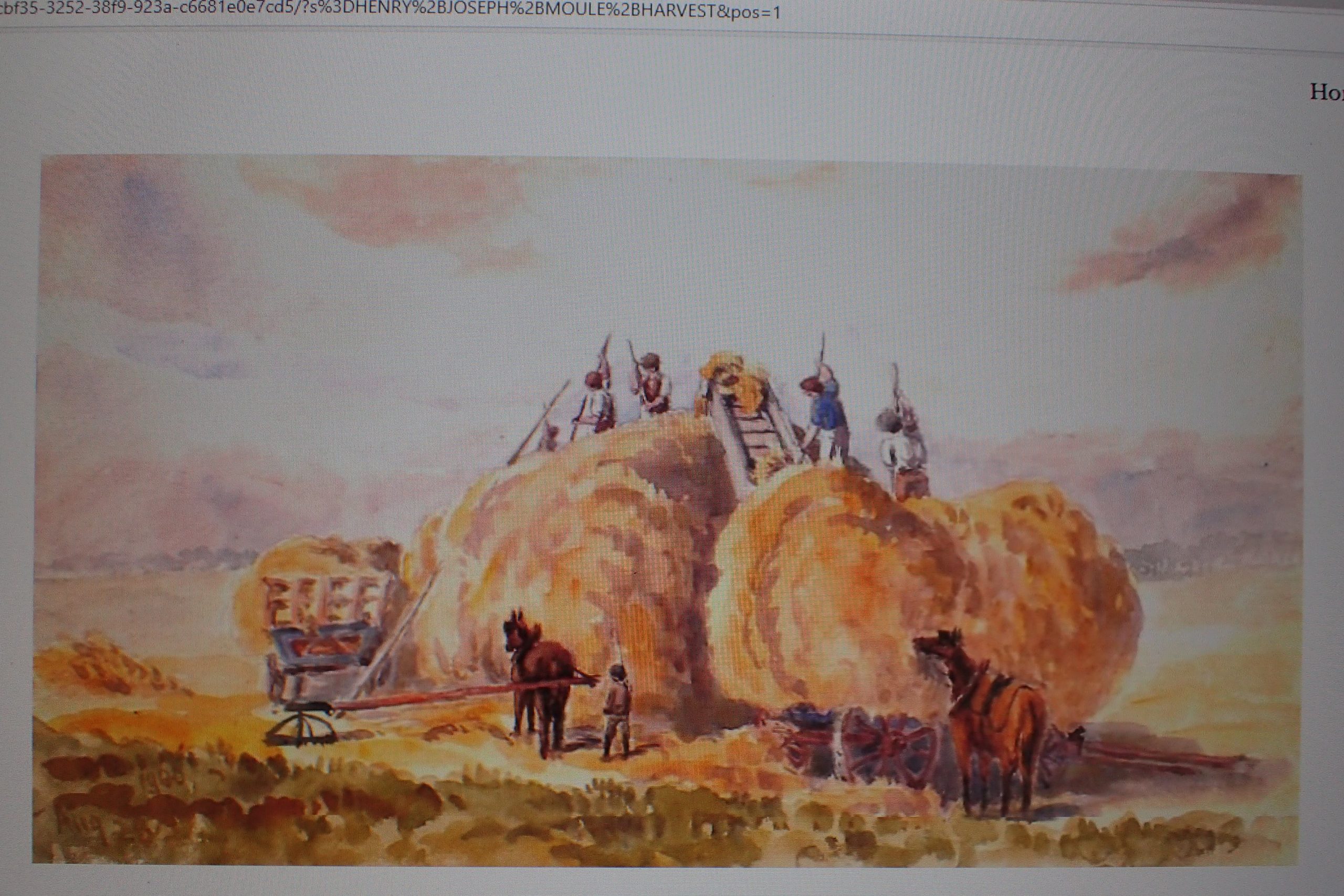

Henry Moule, who had painted for pleasure and to provide gifts for his friends and income to donate to good causes, left over a thousand examples of his watercolours to the museum where they remain to this day.

It is interesting to note that none of his depictions of agricultural workers toiling in the fields include the new steam powered traction engines and threshing machines which were being produced by the foundry at Bourton, Lotte & Walne in Fordington and the Eddison works on the Wareham Road.

For example, a typical harvesting scene, painted by him in 1900, shows all the work being done in Fordington Fields by labourers assisted by a horses and carts with no steam power in sight (Photo 7). His artistic depiction of rural life looked back with a hint of nostalgia to a fast-diminishing world.

IFBG 2.6.2025

Recent Comments